Lessons at 40: Principles I Keep Coming Back To

I turned 40 over the weekend. Oof.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve collected quotes and ideas. I used to jot them in the margins of high-school binders and fill my college notebooks with them. Every few months I skim those fragments and drop the best into the Notes app on my phone. It’s become a bit of a ritual, and I enjoy the entire process.

I’m usually drawn to the pragmatic stuff—principles I can actually use. So this year, as I hit the 40-year mark, I thought I would select a few of my favorites, the ones I keep returning to the most in my work life in case you find them helpful to.

1. Reality has a surprising amount of detail

This is summed up with the old quote:

“We did not do it because it would be easy. We did it because we thought it would be easy.”

There is usually a good reason why things are how they are. Respect the complexity so you can meet it head-on. And the next time you complain about how booking a flight sucks, remember this.

2. Activity will always take the place of a goal

Time spent ≠ Progress. A lot of modern knowledge work is coordinating activities and people.

Make a plan. Send it for feedback. Follow said plan. And so on. But it’s easy to miss the most critical thing—what is the actual goal here, and did we make progress against it?

This is a reminder to push back.

3. Intensity is the strategy

The most successful strategy for long-term success is intensity over a sustained period of time. Nothing else is even close. Picking the right strategy is important, but intensity to move it forward will always drive more outcomes. I find a lot of freedom in this because it places the emphasis on something you can always do – work hard at it.

4. Everyone has something to teach you

It’s easy to poke holes in things and feel smart. Negativity is a constant drumbeat of the media.

Self-select out of it. People are good and the world is a positive place. Wisdom and earned experience can be found everywhere. Just ask and listen.

5. Be a big target for luck

If I could recommend a single thing to actively “do,” it’s this: increase your surface area for luck. Try things, meet people, read books, ask questions, experiment with new tools, be an active participant, seek out expertise. Take an intelligently applied work ethic directed at continual improvement and be deeply committed to learning and teaching.

6. Meaningful = Hard

If something worthwhile appears easy, it means I got lucky. Most things that are meaningful are hard for a reason. The toil is required to access the next level of whatever game you’re playing. Don’t be fooled by lucky breaks disguised as perceived “earned” wins. (It doesn't end well)

7. Slow down and respect everything around you as someone else’s life work

My Opa and my Dad taught me this. Every detail—from the building lobby you walk through to the sandbags over sewer grates—was created out of nothing by someone. Pay attention to the details and appreciate the people behind them and the world takes on a whole new perspective.

8. Be more interested than interesting

I’ve had to learn this again and again. There’s a lot of value in asking questions to understand, not impress. Be curious, not judgmental. Everyone has a story, and they’ll share it—if you prompt it.

9. Accelerate what you can control

Only focus on the things I can directly influence. There is no point in sitting around moping about the state of the world and unfair bounces. Lean into the things I can directly influence, as this always results in the highest throughput. Let the rest fall into place.

Reminder: The future is owned by optimists.

10. Don’t aim to be successful, aim to be useful

This mindset shift is subtle but powerful. People gravitate to those who just want to help move things forward. Chances are you know who the most high-agency people are in your life. Be someone who gets things done.

Success is a byproduct of action.

11. If you let it, the urgent will always overwhelm the important

The best way I have found to fight this urge is to maintain strong habits and focus. But the most progress is made when the important takes priority over whatever the day throws at you. Most of modern work tools like email and Teams are designed to be optimized for the urgent—take back control of your day and the productivity will follow.

12. Invert: Aim to minimize negative outcomes

Charlie Munger’s idea to “invert” is always with me when I make strategic decisions. Avoiding failure is often easier than defining exact steps to a successful outcome.

Ask: What are the worst outcomes here? Then plan to avoid them.

13. Choose things with a good base rate of success

The average of how others perform is often the best predictor of my results.

I want to be in situations where the base rate is attractive—where I don’t need to hit a home run to win. This idea of picking a good base rate from Brent Beshore has stuck with me. Why choose games with bad odds?

14. Win and help win

The world isn’t zero-sum. Helping others win is just as rewarding as winning yourself. Helping win is more than just being a cheerleader. It’s playing an active role in supporting, connecting, and building up the people around you in their careers.

15. Pick opportunities with asymmetric outcomes

There are endless opportunities. Look for things where the upside is 3–4x the downside. Rule #1 of investing time or money: don’t get wiped out. Rule #2: look for asymmetric upside. And if you don't think its there, avoid forcing it to make it look that way. The best opportunities don't make you squint.

16. Life is messy

People, business, relationships—me included. Expect chaos. Meet it with grace. Setbacks are part of the game, not the exception. Don’t fear the messiness—navigate it. The truth is, if things feel smooth, its either temporary or you are missing something.

17. Never stop exploring

“Your archive paints your future, so build a rich repository.” I love that line. Build an deep archive of ideas, notes, experiences. Revisit and remix what you’ve learned. Life is full of unexpected connections just waiting to be made, so build a big internal library.

18. In business, maximization is the minimization of joy

I don’t thrive in environments where the game is endless optimization. That’s probably a “me” thing, but I have found that individuals and teams really come alive when they apply creativity to how they approach or tackle problems first. Optimization is part of the game—but not the whole game.

19. Don’t bet on stasis

The world is always changing. Bet on that. If something “isn’t done that way,” it doesn’t mean it won’t be. Embrace change. Be skeptical of blue-chip certainty and Excel models with perfect curves.

The Army of Interns

A common mistake I make when experimenting with AI is treating it like a question-answering machine.

Google has trained us to think this way. You type in a query, and it hands you a trail of crumbs pointing in roughly the right direction. You search, browse, and assemble the puzzle pieces yourself. It's an ingrained habit.

AI, of course, does a surprisingly good job of this too. If you ask Perplexity or ChatGPT something like "What is the history of tariffs and their economic effects?" you'll get a detailed, coherent answer almost instantly. Google will give you that too, eventually—though after you've sifted through multiple tabs. The end result, though, feels quite similar: you have a question, and you receive an answer.

But if that's all you ever do with AI, you'll soon hit some limits. The responses can feel vague, overly general, even occasionally wrong. You might find yourself underwhelmed.

Tyler Cowen explains this behaviour well:

"They're asking it questions that are too general and not willing enough to give it context, so they end up insufficiently impressed by the AI. But if you keep on whacking it with queries and facts and questions and interpretations, you'll come away much more impressed than if you just ask it simple questions. At the end of the day, if you do that, you'll be asleep on the revolution occurring before our eyes: AI is getting smarter than we are. You'll just think it's a cheap way to achieve a lot of mid-level tasks, which it also is."

So if AI isn't just an answering machine, then what exactly is it?

Bring in the Army

A better way to think about AI is to imagine you have an infinite army of smart, eager interns.

They're enthusiastic but require direction.

Give them vague instructions and you'll receive vague results. You wouldn't send a one-line email saying, "Figure this out" and expect great outputs. Instead, you'd carefully explain the task, detail precisely what you're looking for, and provide useful reference materials.

In other words, it's less about getting answers and more about enhancing the quality and speed of your own thinking, leveraging your own knowledge and context. This starts with proper prompting, but its more nuanced than that. If you use ChatGPT o1 or DeepSeek you can observe the chain of thought reasoning as it processes in real time. You can watch the model think and process your query as it compiles a response. What you'll notice is that at the heart of great prompt is great context. Its hard to prompt AI's with what we don't know. The more you bring to the party, the better the answers will be because you can spot the errors and fine tune.

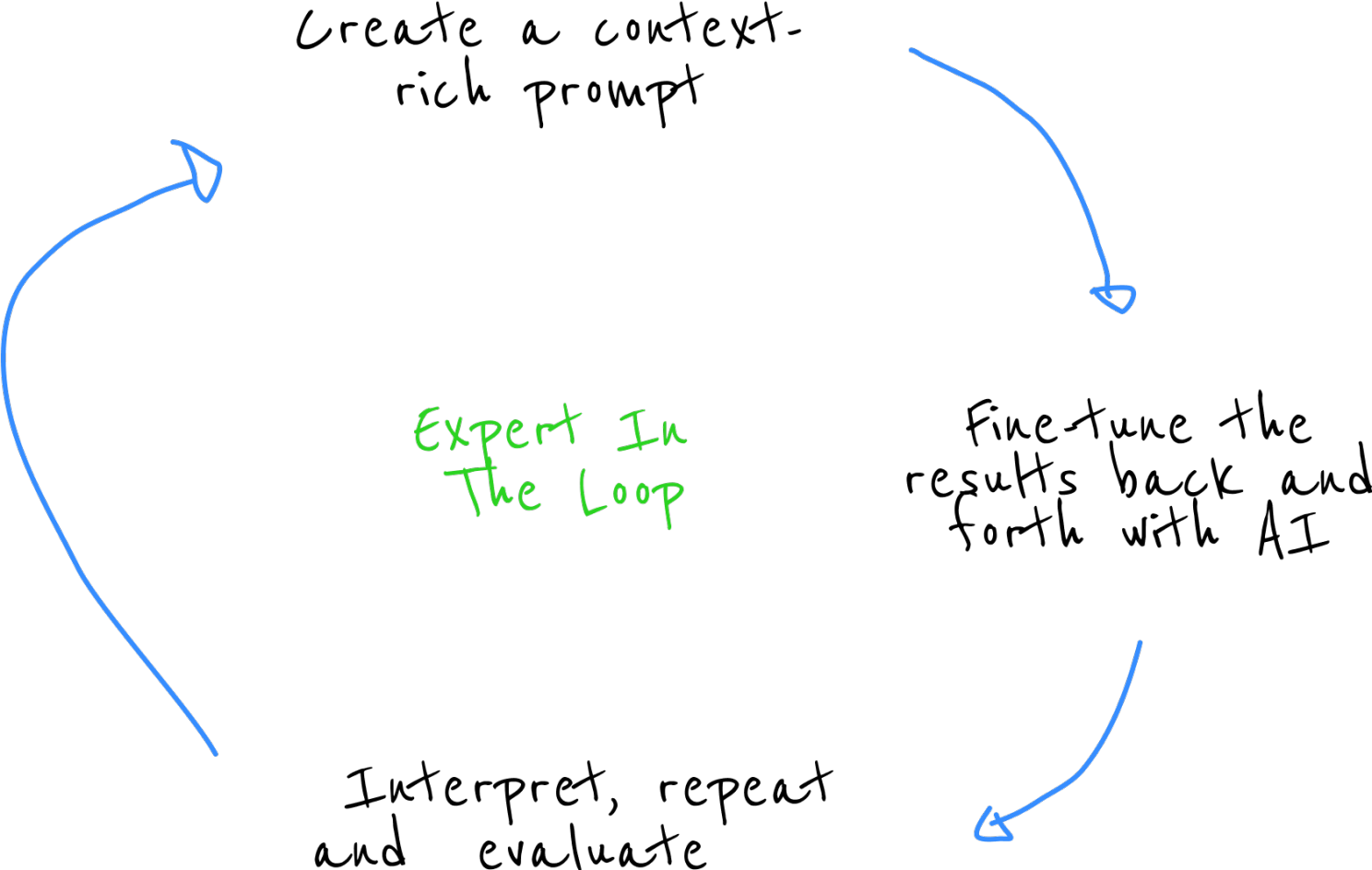

Expert In The Loop

Our brains excel at making relative judgments, not absolute ones. It’s easier to say “this is better than that” than to assign an objective score. This is why expert taste, in any field, is built on comparisons, not formulas.

(Its hard to describe how tall someone is. But its a lot easier to look at two people and say who is taller. Its clearer)

Taste isn’t built on checklists. It’s built on contrast. The best writers, the best designers, the best decision-makers—they don’t just know what’s “good.” They know what’s better.

That "skill" we are poking at is defined as tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge are the insights people gain naturally through experiences, interactions, and observations without consciously realizing it.

AI can write an essay, but it doesn’t know what makes a great one—it just mimics patterns. If AI is good at formulas and automation, then human advantage comes from judgment, intuition, and taste—things learned over time.

An expert chef doesn’t measure every spice with precision; they sense what the dish needs. An AI can suggest a recipe, but it won’t invent a new one the way a seasoned chef will. Pattern matching, or reverse pattern matching, is foundational to expertise.

A radiologist will interpret a x-ray a lot better than a lay person, but can leverage the rapid and comprehensive knowledge of an AI tool to speed up the process.

Having an expert-in-the-loop, applying tacit knowledge and experience, will always create a better result.

Here is another example. When hiring a top law firm, you're paying for more than precedents and intellectual horsepower; you're paying for the nuanced judgment and deep experience of the partner managing your file. Large language models can handle the first parts efficiently, but the essential human expertise is the secret sauce. Tacit knowledge is what allows the process to function at its best.

Here is the interesting thing. Tacit expertise makes humans valuable in an AI world as the "expert in the loop"

Here is how this looks at a high level:

Leverage, not Answers

AI will keep getting better at the explicit things, the measurable things, the problems we’ve already defined. But the the intuitive leaps, the gut-feelings will remain uniquely human.

The best results are found when you really push into the details and continuing to refine the answer set. One thing that I have found to be surprisingly helpful in delivering higher quality responses is using phrases like "Think Hard" and "Think Deep and Longer" and requesting revisions when I think the quality isn't up to snuff. For some reason this is hard to remember to do! It isn't a normal pattern if you are used to using search engines for discovery and learning.

The future won’t belong to those who treat AI like Google, asking questions and hoping for answers. It’ll belong to those who learn to direct this infinite army of interns and pair AI’s tireless pattern-matching with their own taste and judgment.

In other words: don’t outsource your intuition. Leverage it.

How To Prepare For a Very Different World

Until recently, a new graduate had a direct path. Go to college, study hard, get a good job. Ambitious students did this for decades, and it generally worked. It’s baked into our cultural DNA.

But AI is rewriting that script, and if you want to stay ahead, you’ll need to think differently. When fields like computer science, medicine, law, accounting, and business all face massive upheavals, where do you focus? It’s not an easy question.

And it’s not just a question for students. Everyone will find themselves squeezed into a similar position, and probably faster than you think. The pace of AI is hard to wrap your mind around. The top AI models are getting remarkably smarter and cheaper to train and operate, and they are not slowing down. AGI will probably be achieved in the next year or so, if it hasn’t already.

How to avoid picking the wrong things

There are two ways to look at this.

One is to choose a field, follow the usual steps, and adapt as AI transforms it. For a long time, this has worked reasonably well.

The second way is to try and front-run where AI is headed and focus your time on things that will become more valuable in the future. This is, of course, hard to do – like trying to catch a wave before it crests.

So how do you avoid wasting time on the wrong things? By focusing on fundamental skills. There are certain skills that will matter no matter how things play out. These building blocks give you leverage. If your goal is to maximize the surface area for opportunity, then you’re much less likely to find yourself left behind.

Let's explore a few of these further.

1. Take agency with what (and how) you are learning

Traditional education will not be able to handle the rate of change, so you will need to work around them to learn faster. Large Language Models (LLMs) are best at coordinating deep learning if you use them correctly. The bar for understanding entire industries is low, even for professionals working in them. Use AI to rapidly build competency in connected domains. I like to use Google’s NotebookLM as a centralized repository for research papers, articles, podcasts and basically everything else I can find on a topic – after enough primary sources are added, I find I can hone in on the key concepts and build a systematic approach to learning. These tools will only improve with time. Use them.

2. Develop the skills required to coordinate systems

AI will automate routine tasks, but critical thinking and complex problem-solving remain highly valuable. Focus on learning skills like critical thinking, problem-solving, data literacy, and creative collaboration. Develop soft skills (communication, leadership, empathy), which are harder for AI to replicate but crucial for managing AI systems.

Think about the architect in a small firm that adopts AI to generate building layouts based on zoning rules and design preferences. While the AI can provide quick drafts, it can’t capture the full context of client needs—such as how a space should feel. The architect’s role shifts from spending hours on drafts to guiding the design process and working within real world people constraints. AI enables the process instead of replacing it.

The difference between AI and past technological advancements is that it doesn’t just make work more efficient—it also provides real-time feedback and guidance, almost like an editorial assistant. AI can help you refine your ideas and decisions as you work. In a world where humans, AI agents, and tools need to collaborate, the key skill to develop will be learning how to coordinate and harness these resources in the right ways.

3. Master the ability to communicate with AI

For most tasks, AI won’t replace humans but will augment them. Once you’ve used AI tools for a while, you’ll notice their strengths—pattern recognition, data synthesis—and their weaknesses, like handling nuance or creativity. The key is learning how to push AI beyond surface-level outputs by giving it better instructions. This means mastering prompt engineering, building workflows with AI agents, and automating routine tasks.

Take writing, for example. AI can quickly generate article drafts or summarize research, but left unchecked, the result feels bland or repetitive. Instead, guide it by crafting prompts that nudge it toward your specific style, then continually refine the output. Over time, you will find more success by switching to more of an AI editor, leveraging the tool’s speed while ensuring the final product still carries nuance and originality. The better you communicate these intentions with AI, the more useful it becomes.

Instead of starting with a written prompt, I have found that by using ChatGPT’s Advanced Voice Mode I get better results by just talking to it for 20 minutes or so on a topic to “start” a draft topic. I then upload the entire train of thought and ask for feedback. This creates a dialogue and a refinement process that is very different than pure input/output. The results are strikingly different.

4. Practice and build creative things

AI can remix existing ideas but has trouble with true creativity. That’s your edge. To create something new, you need to connect and build ideas in original ways. Learning by doing is is like a super power—it forces you to grapple with edge cases and develop a deeper understanding.

LLMs are, at their core, prediction engines. They generate outputs based on patterns from prior data, but genuine creativity requires combining and remixing ideas in ways that machines can’t predict. To make interesting things, you need to build your own internal library of creative references through experience and continual exploration and use AI to bring them to life.

While this has always been important, AI tools now make it easier than ever to get started in creative fields. The catch? With creativity more accessible to everyone, the goal posts for what is considered good will shift along with it. There will always be a market for good taste.

5. Start with first principles

A common mistake is to try and retrofit AI onto existing systems. But problems can now be solved in ways that were impossible before. You’ll never see those opportunities if you’re stuck thinking about how to optimize what’s already there. Most people see AI as a tool to improve existing processes, like adding a faster engine to an old car. Instead, ask: If AI were at the core, how would I design this differently?

This isn’t easy. Humans are naturally anchored to what exists. But if you were starting from scratch today, would you still design schools, hospitals, or companies the same way?Probably not.

6. Think of AI as your co-founder

In the past, if you wanted to build something big, you needed infrastructure—offices, servers, employees to handle everything from marketing to operations. Now, with AI tools and agents, you can automate large parts of that work. You can launch and run a business that would have required a whole team just a few years ago.

AI is making the “one-person company” a reality. This isn’t just about efficiency; it’s about leverage. You can build faster and iterate quickly because you’re not weighed down by the overhead of traditional scaling. A small team can punch far above its weight, using AI to handle tasks like customer service, product development, and data analysis.This inverts a lot of assumptions in traditional competitive environments, but particularly in regards to traditional pricing and business models. Pay attention to any industry that is billable by the hour today. The Red Queen effect is real.

Onward is the only direction worth traveling

So where does that leave us? The best way to prepare for a world shaped by AI is to stay adaptable, keep learning, and build things. AI is moving fast, and your biggest advantage is curiosity and the ability to adapt.

There’s no step-by-step guide—just experiment, take risks, and stay open to new ideas. High agency matters more than ever. Technology shifts start with individuals, not institutions. You have the advantage of being able to move quickly and carve out your own path. Progress is less about playing by the rules and more about figuring things out as they unfold. After all, there are no cheap tickets to mastery.

There are no cheap tickets to mastery

Here are a few obvious things:

If you want to write better, then write more.

If you want to improve reporting, do the work to clean the data.

If you want to be a better manager, meet with your people.

If you want to test an idea, talk to your customers.

Nothing radical there.

And yet, its never been more easy to avoid the hard step. Instead of doing the thing, you search for ways around doing the thing under the tempting guise of finding a better way.

I find myself slipping into “optimize mode” all of the time. I’ll look at a new problem and jump to “There has to be a shortcut.” or “How do I make this easier? There has to be a thing to make this faster”

Generative AI tools make it even easier to fall into this thinking. “What if we just automate this? Skip this step and let ChatGPT write it?”

But this buries the point. The marketplace rewards quality. And quality is an output of clear thinking. Sure, ChatGPT can improve your process or provide a creative assist or edit. You should definitely use these tools.

But you first you need to discover where the weak spots are. These are uncovered by doing the work to know where the edges are. Differentiated results come from diving into the problem and wading though the surprising amount of detail beneath the surface.

There are no cheap tickets to mastery.

Be A Default-AI Employee

If I had to make a single bet on what will be one of the largest shifts in an AI enabled world this is it: Companies that build and train employees to be Default-AI will outperform those who don’t.

What is a Default-AI Employee?

I define Default-AI like this: For all general and specific work tasks, the employee integrates generative AI capabilities and platforms as the default tools for their job.

Not internal training documents, existing company tools, or standard operating procedures.

Let’s take a Research Analyst as an example. Her primary job should be to figure out how to leverage AI tools to assist her research quality and output as a first priority. She would use blend of company owned internal tools and general purpose platforms like ChatGPT to improve her quality and speed of analysis.

Or consider a Customer Support rep that is responding to customer issues. A Default-AI employee would quickly identify that they could leverage an LLM trained on internal sales calls to rapidly troubleshoot common customer issues. (We built a version of this for ourselves at Rescue Payments)

How this is different

The crucial differentiation here is that the Default-AI company places the responsibility to determine how to leverage AI tools on each individual contributor, not as a top-down directive of management.

In the pre-AI world, companies required employees to use the tools selected by company and be trained on internal procedures for the role.

The inverse is true today.

Employees should be empowered to deconstruct their work objectives and sort them into tasks that require human action and those that can be enhanced with AI. This is not a one time act – as the tools evolve and get better, the individual is responsible for adapting the workflow to take advantage of it. The only way that can happen is if that responsibility extends to the person closest to the task. This is not typically a manager.

Said another way, Generative AI fundamentally rewrites workflows because it shifts the responsibility to better, faster, smarter, or less expensive from the organization to the individual.

How to build a company around this concept

Let’s break this down further.

In order to accelerate this shift, it requires an organizational capability to be able to create and rapidly connect AI tools and apps internally. Forming a small internal development team to support and stitch together employee-driven ideas. The Default-AI employee can leverage this team to rapidly deploy tools and test them in their day-to-day.

Here is why it matters.

If you are making a hiring decision today, willingness and capability to be Default-AI contributor should be part of the criteria.

At Rescue, we ask questions like "When was the last time you used an AI tool for your job?" and "What parts of your previous role could have been substantially improved if you had full control over how you did your job and what tools you used?"

Today, the Default-AI mindset is specifically associated with knowledge work, but will soon expand to other categories. One could imagine a plumber taking a Default-AI approach to their daily tasks and quickly building a proprietary stack that improves their quality and speed.

Evaluating this is nuanced and specific to the role.

But the returns on hiring talent through this lens will be outsized.

Another Interesting AI Observation: Time = Quality?

Researchers recently took random sample of 200 patient questions from the AskDocs forum on Reddit.

The asked both human doctors and ChatGPT to provide answers to the questions. A clinical team assessed the responses, focusing on the quality of the answers and the level of empathy demonstrated.

ChatGPT emerged as the clear winner, with evaluators favouring its responses nearly 80% of the time over the human doctors.

The insight here is not that doctors aren't empathetic. It's that ChatGPT has unlimited "time" to craft a proper response. Unlike humans, generative AI isn't limited by fatigue or effort perception. Patients often equate the amount of time spent explaining their diagnoses with the quality of care, as it fosters a feeling of empathy and clarity. Human doctors, used to running on tight schedules and billing on a time basis – are trained to be more blunt and straightforward with their bedside manner. The outcome is a patient perceived quality gap.

This offers up an interesting thought experiment – what other things in our day to day lives will benefit from more time? The ability to craft thoughtful, polite employee reviews from bullet points is an interesting use case. Or a CFO, leveraging GPT-4 to instantly generate and chart financial trends from a data set, so she can spend more time on diagnoses and interpretation.

The inverted way of looking at this is: What parts of my work would improve if I had twice or even ten times the usual time to spend on the delivery?

Activity Will Always Take the Place of A Goal

A lot of modern knowledge work is coordinating activities and people. Make a plan. Send that for feedback. Set the meeting for next Tuesday to review. Follow said plan. And so on.

But its easy to miss the most critical thing – what is the actual goal here and did we make progress against it?

I see teams slip into the rhythms of "doing things" and equate it with making progress. These are not the same. Often they are the opposite.

Activity will always take the place of a goal.

Set the objective. Revisit it. Not just tomorrow or at the end, but every day.

Optimized to Death

When a team is faced with a new problem, the instinctive reaction is to start measuring a bunch of things. KPI's, dashboards, OKR's, analytics etc.

Data is helpful and it tells a story.

But it is a story.

When you introduce metrics, someone has to interpret the data. Interpretation means meetings and debates.

Analytics don’t tell you what to do, they show a version of what happened. This isn't necessarily bad, but it does have a crucial unintended side effect. It takes a lot of time to make sense of it all.

The most important factor in launching new things is speed. Your goal is to get to the other side. Generating momentum is crucial. Great ideas can get optimized to death. Creativity is stifled by endless discussions and prioritization sessions.

What matters most is being decisive. Effective teams will respond quickly if the initial decisions prove out to be wrong - in early stages your instincts will be right. Relying on data will just slows things down.

Trust your hunches and talk to your customers. Optimization can wait.

Understanding Constraints

There are two consistent ingredients in successful technology projects:

- The project team places a deep emphasis on completely understanding, unpacking and respecting the real-world constraints on the business and project. There was a reluctance to trust simple answers.

- There is a strong bias to action

The truth is, the right solutions end up being composed of a mix of best practices, off the shelf tools, and existing technology combined with dogged problem solving, hacks and new ideas. It's rarely the result of applying a simple "ah-ha" answer.

I call this process of discovery "creative assembly" and it's at the heart of driving performance. It's an intentional, active and creative act.

Intuitively this makes sense. Complex things are messy. If it isn't, it's probably because you got lucky or you're wrong.

Where teams get stuck is that they start to place too much emphasis on the net new things (technology, techniques, hiring) and skip over the existing realities (embedded tools, workflows, market). Every company is different, but they all have hidden constraints.

To borrow from mathematics a bit, it's better to think of creative assembly as a combinatorial process. Meaning that most of the obstacles are problems of selection, arrangement, and operation within a finite system of constraints.

Innovation is a result of the discovering the right combination of things, not changing the elements that make it up. Choosing how and what to mix (and in what order) is at the centre of a successful strategy.

Get to know your constraints. The progress will follow.

The Infinite Training Machine

Last year I spent a few months reading through all of Berkshire Hathaway's Annual Reports spanning the last two decades. Sprinkled amongst the financials are a wealth of anecdotes, theories and mental concepts written in Warren Buffett’s trademark matter-of-fact style.

One of Buffett's philosophies on how Berkshire makes investments particularly resonated with me.

"If we have a strength, it is in recognizing when we are operating well within our circle of competence and when we are approaching the perimeter. Predicting the long-term economics of companies that operate in fast-changing industries is simply far beyond our perimeter. If others claim predictive skill in those industries — and seem to have their claims validated by the behavior of the stock market — we neither envy nor emulate them” - 1999 Annual Letter

I love how he phrases this concept – the circle of competence. In a previous letter back in 1996, he explained further:

"You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital." - 1996 Annual Letter

I think a lot about expanding our circle of competence across our organization at Versett and individually. But there is also freedom in identifying the boundaries and understanding them inside and out. Depth is more important than breadth.

Three of the hardest words in the English language are “I don’t know”. In this connected, ChatGPT-enabled environment, information is a few prompts away. This contributes to a dangerous illusion – that after a few hours of digging, it's possible to expand your circle of competence. But boundaries don't stretch overnight.

ChatGPT doesn't give us speed, it gives an accessible and malleable surface area to explore deeper. An infinite training machine. Resist the temptation to "dip a toe" into a concept or problem, aim instead for expansion and mastery of the core concepts. Create and test things. Learn by doing. Chip away at the boundaries by digging deeper into the first principles.

Bottom line: Circles of competence are built not acquired. Just because it's accessible doesn’t mean it's the best way to learn something that lasts.

Avoid the Project Trap

The worst thing that can happen to a team is that their work devolves into projects

Projects ask:

- When does it need to be done?

- Who will do it?

- How will we resource it?

These are all important considerations. But they skip the crucial first step of driving at "why". Just because something can happen doesn't mean it should.

Instead start with questions like:

- Why is this important?

- What are we saying "no" to if we start this?

- What would this look like if it were easy?

- What is the simplest way to do this? What's the most robust?

- How do we know if we are right?

The Project Trap is a group mindset that tricks teams into believing that if they check the boxes on projects it will automatically result in driving outcomes.

In reality, only the right actions will move the needle. Projects are just a container for actions – so consistently evaluate if they are the right ones.

Find A Way

I've found that whenever a group faces a big decision, there are two types of reactions:

- Group 1 finds reasons. Reasons why it will work. Reasons why it won't. Explanations, experienced views and opinions on the why's and why not's.

- Group 2 finds a way.

Reasons are easy to find wherever you look. This is especially true for smart people. There always good reasons to do or not do something. Intelligent minds are trained to think about pros and cons. Want to sound smart? Give informed reasons why something won't work. Pessimism comes naturally because most ideas are bad. Your hit rate will be high.

But the trajectory won't.

Breakthroughs don't require reasons; they need someone to forge a path. To find a way through the complexity and ambiguity and act.

Reasons delay action.

Action yields information.

If you come up on a complex decision, get past the reasons and find a way.

Action Yields Information

Managers get people together to talk about a problem. They divvy up the responsibilities, discuss risks and facilitate.

Leaders, however, inspire action. They tear down roadblocks. Get things moving. Progress starts when big things break down into smaller achievable chunks.

Managers focus on the process. Leaders create momentum.

Great teams win because they get off the ground and start learning. Action yields information. The first few steps create the foundation for the next hundred.

So don't wait, go.

"That's not my job"

A few weeks ago Barack Obama was asked to give career advice.

“The most important advice I give to young people is … just learn how to get stuff done,” Obama explained. “I’ve seen at every level people who are very good at describing problems, people who are very sophisticated in explaining why something went wrong or why something can’t get fixed, but what I’m always looking for is no matter how small the problem or how big it is, somebody who says, ‘Let me take care of that.’"

The more senior you become, the more your job involves filling gaps and handling situations that are complex and unclear.

You are here to make your organization successful (whatever that means at that moment). Finger-pointing and questioning "who does what" stalls progress by putting the actual work aside and placing focus inward.

High-performance teams dial in on the tasks ahead, divvying up responsibilities and making incremental progress on the goal. Delegating is an important tool, but can also devolve into abdication. Sometimes things just need to get done.

One time on a job site I saw my General Contractor driving around the site collecting garbage. I asked him why he was doing it. "It needs to be done to keep things moving"

Peter Drucker notes that “Plans are only good intentions unless they immediately degenerate into hard work”

Find the gaps, fill them, and move on.

Vitruvius, Principles and Craft

Poggio Bracciolini knew it the second he flipped through the first few dusty pages.

He had spent days holed up in a Swiss monastery searching for writings that had been lost for centuries. As an avid manuscript hunter and former secretary to multiple popes, he was obsessed with finding the forgotten books of history.

But this one was big.

What he had unearthed was the only remaining copy of De Architectura, a comprehensive book on architecture by early Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius. This discovery in the 15th century and subsequent circulation in the intellectual circles of the Renaissance played a significant role in shaping the architectural principles that transformed much of early Europe. Bracciolini's finding not only influenced architects but also caught the attention of artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, who was so inspired by Vitruvius's ideas on proportion and harmony in architecture and the human body. This fascination led to the creation of da Vinci's famous drawing, the "Vitruvian Man" seen in the image above.

Vitruvius was very hands-on and wrote deeply on the principles of his craft. What I find his intriguing about his ideas is that they remain directly relevant to designing things people love today, even though they were formulated over 2,000 years ago. The same ideas that sparked Da Vinci jump off the page now.

De architectura provided guidelines for constructing buildings, but Vitruvius went a layer deeper. He stated that a building must possess three essential qualities: firmitatis (stability), utilitatis (utility), and venustatis (beauty). These principles, now known as the "Vitruvian Triad," continue to be taught in architecture schools today.

Read this excerpt from Chapter 1 of *De architectura* and observe the parallels to contemporary work (emphasis is mine):

1. Architecture is a science arising out of many other sciences, and adorned with much and varied learning; by the help of which a judgment is formed of those works which are the result of other arts. Practice and theory are its parents.

Practice is the frequent and continued contemplation of the mode of executing any given work, or of the mere operation of the hands, for the conversion of the material in the best and readiest way.

Theory is the result of that reasoning which demonstrates and explains that the material wrought has been so converted as to answer the end proposed.

2. Wherefore the mere practical architect is not able to assign sufficient reasons for the forms he adopts; and the theoretic architect also fails, grasping the shadow instead of the substance. He who is theoretic as well as practical, is therefore doubly armed; able not only to prove the propriety of his design, but equally so to carry it into execution"

What an incredible piece of writing.

Vitruvius’ insights on theory and pragmatism are directly relatable to any product team today. His concept of being “doubly armed” is a reminder that theory and execution are tightly linked. Spending too much time in either camp will hinder your ability to build the right things.

I remember a project where the product team leaned in heavy into theory. They had done study after study. Deep market analysis. Interviewed every stakeholder. Applied the right frameworks. But after months nothing was actually built. This information was helpful but it was also stale – it lacked the spark that you can only get by doing. The overemphasis on theory was well-intentioned but actually increased the risk of execution.

It was out of balance.

Skip theory all together and just start building things blindly and you will miss out on the hard won experience and understanding that can help shape a better result.

Engage in pure theory and avoid shipping things and you will fail to make any meaningful progress. This will lead into "work about work" instead of the product.

Great products are the result of intention and focus. Intention blossoms with balance, being "double armed". Holding the tension of being a student of your craft while always being rooted in pragmatic execution.

So take a page from Vitruvius and evaluate if your team is striking the right balance and course correct if you are off track.

PS. If you find these principles interesting, the rest of De architectura is equally great.You can pick up a copy for cheap on Amazon. Its a fascinating read.

Don't build a dam and wait for a river

In the face of a sudden shift like AI, it's natural to feel compelled to take action.

The tricky thing is figuring out what that thing is.

Humans excel at pattern recognition, but there aren't many patterns to observe yet – everyone is watching this unfold live.

This makes for a frothy environment. A common mistake is to launch a flashy initiative just for the sake of doing something. This approach rarely succeeds. (It's like building a dam and waiting for a river)

Why?

- First order effects are not always the most interesting. The history of platform shifts (electricity, internet, mobile) reveals that the second-order shifts return the greatest results. Google was the 15th search engine.

- Your context is unique, and context is where value is created. It's not one-size fits all. What works in one spot may not work in another.

Instead of focusing on one big thing, split it up into bite sized chunks. For many company's, the most significant impacts will spring out of existing workflows that get supercharged.

How can you identify the right ideas? Improve your team's fundamental understanding of how these tools function. Promote experimentation. Distribute pattern recognition across the company. Play with new concepts.

Over time, the substantial opportunities will gradually become clear.

And when you spot the river, act fast to build the dam.

Inputs

Nobody is here to make good products.

We’re all here to make great products.

But what makes a product great? It's a combination of things – feel, utility, context, pragmatism, charm. Greatness is about getting the dials of dozens of these elements tuned just right.

How do we get there?

One helpful tool is to consider your inputs.

If you’re making a caprese salad, the quality of your tomatoes, basil and mozzarella matter.

The same logic applies to products. Greatness is a function of applied creativity. And at its centre, creativity is an exposure game – your inputs matter. So one path to great is to maximize the “retrievability” of analogous things that are similar to the problem you are solving. Pay attention to the things that make it specifically great. Humans are naturally good at this – we are pattern matching machines.

Better inputs, better products.

But wait. There is also a multiplier – collaboration. When a few people (or a lot) combine inputs, it widens the breadth of our thinking. Link up with people close to you.

Focusing on inputs is a daily practice and a fun one. How do you stay fresh?

Self-Serve, the not-so-obvious cheat code to growth

Percival Everitt had an idea.

Walking through a London railway station in 1883 he decided to purchase a postcard, the newest craze in Europe at the time. But it was late in the evening, which meant an early morning visit to the corner store. He started to think that there had to be a better way.

Everitt got to work. He dreamed up a machine that allowed a customer to purchase a postcard by entering coins into a slot. The first version was made of cast-iron, towering over six feet tall and weighed hundreds of pounds. It wasn't the most elegant but it worked. His machines sold a postcard for a penny and provided unmatched convenience to commuters.

It was a hit. Everitt had just invented the modern vending machine.

Rail passengers loved them. European authorities had recently agreed to standardization of postcard size which made them particularly well-suited to coin operated machines, but nearly everything else was fraught with challenges.

"An original feature developed by Everitt was that when machines were out of stock, they automatically closed the coin slot so no customers could lose their money...He also tried to thwart attempts to use slugs, by making the weighing scale in his machines more exact. He also placed machines in high traffic areas, such as near railroad stops, so that rail employees could help police the machines"

The company ended up being a big success. By 1901, the company had placed at least one machine in nearly all of Britain’s more than 7,000 railway stations.

Everitt stumbled on a powerful idea: that things like convenience, control and availability were important factors in a buying decision. But it also proved out a fundamental principle – there is tremendous market power in offering a self-serve option to customers.

So what is self-serve?

At Versett we have observed a subtle but powerful shift that impacts almost every industry in the world, including yours. Businesses are now increasingly required to give their customers a "self-serve" option. This has been further compounded by the pandemic in recent months. The ones that do this better will leapfrog the ones that don’t.

And yet we see examples of companies failing at this all of the time:

- Why do I need to call my internet provider to select a new speed package?

- Why can’t I buy a book online at my local bookstore instead of Amazon?

- Why does my gym not also give me workouts to do at home or when I am on the road?

- Why can’t I figure out if the BBQ I want is available at the Home Depot near my house?

These scenarios all have one thing in common. In each example the company has opted to not allow the customer to complete an action outside of their prescribed methods. In many cases this is at odds with what a large and growing segment of their customers would prefer. They are not letting people self-serve.

Self-Serve means that customers can research, compare and transact with you on their terms. It's about giving customers the ability to interact with you and your products how they want. Now of course people should be able to choose to talk with a person if they need help selecting or need support. But it shouldn’t be the only option.

Let’s point to another example. One of the biggest shifts in self-serve in decades was e-commerce, which gave customers the ability to shop from you online , on-demand. But e-commerce's best trick is not that it gives you instant access to a broader selection of products, it's that it allows you to research and evaluate between options better. Let's say you wanted to purchase a TV at Best Buy. You would probably end up walking down the street to another retailer to compare other options. The internet flattens this. You can sort and compare everything on your iPad sitting on your couch.

That's a very powerful ability and it's a secret of self-serve. Most firms are not taking advantage of it.

If what is popping into your head right now is "Yeah, but I want to be able to control the experience" or "That will never work, my sales team is what makes the difference" then it's more likely you have a positioning problem. It's not that your customers are not looking for self-serve, it's that your company doesn't have the capability to do it. If your firm has to avoid self-serve to be successful then you will eventually be beat by a firm that is better positioned and doesn't have to. Self-serve capabilities are like a cheat code. Do it right and it's an instant capability.

Let me show you this in practice. give you another example. One of our clients recently rolled out the ability to purchase products online. They also enabled the capability to live-chat at any point on the site. What was surprising to management was that over half of all sales in the first six months were purchased through the chat function, with the other half through e-commerce directly. Customers could choose to either shop in a store, buy directly online or chat with someone to figure out what to buy. Self-serve gives the customer the ability to choose how and where they want to buy. Choice increases marginal conversion and reduces churn.

I once heard that strategy is a company's answer to the question: What can we do that's really hard? Enabling true self-serve capabilities is naturally challenging because many of the elements that enable it to work are disconnected. Inventory, pricing, marketing, offline-online hand-offs. It often requires rethinking the complete customer journey and making changes to those experiences along the way. The entire experience matters. Just because a customer could technically fumble their way through your terrible website and somehow connect the dots and make a purchase themselves, doesn't make it 'self-serve'. Just look at our recent Insurance Trends report to see how many new entrants are solving self-serve problems in this market.

But there is tremendous potential value in doing this right. Self-serve generates economic leverage, provides a better customer experience and protects against startups and new entrants to markets that are approaching this from the bottom up.

Key Takeaways

- Self-Serve means that customers can research, compare and transact with you on their terms.

- Companies that create self-serve centred businesses will outperform those who don’t

- Evaluate each area of your business to determine opportunities to better allow customers to self-serve

- Ask your customers where they experienced problems purchasing from you. Hint: it almost always involves payment, product selection or availability.

- Start small – look for opportunities to address areas where self-serve can be implemented. It could be an FAQ or support section or as simple as adding chat to e-commerce.

Recipes vs Preparations

Ferran Adria is considered one of the world's best chefs. In 1994, he opened elBulli, a 3-Michelin starred restaurant in Spain that won “Best Restaurant in the World” five times before closing in 2010. Adria was a prolific innovator, ushering in the concept of “molecular gastronomy” and pioneering many other new kitchen techniques (you can thank him for all of that foam you see on food these days). He was also prolific, creating over 1,846 dishes over the course of his career at elBulli.

I heard an interview with Adria a few years back and he said something that has stuck with me ever since. When asked about how he approached making his recipes, he responded:

“We don’t create dishes, we create preparations. This way we make many dishes.”

Preparations. Now that's an interesting word. Adria approached creating great food as a result of refining the basic building blocks of ingredients and then combining them in interesting ways. He found that if you mix sodium alginate with calcium, a gel forms. This gel can be transformed in all sorts of ways – when added to other preparations the result can be wholly new. If you start from a recipe, all you get is a recipe with a twist. Adria flipped the script and developed a strategy for adaptability and iteration, giving him the platform to respond as new information came in.

When operating a business it can be tempting to look for recipes. It's human nature to seek out the answers or playbooks that give us a sure bet or a clear path. Everyone wants a map. And to some extent, the recipes that make up the bulk of business writing today provide some insight, but often fail to prepare for a changing world. Why? Your business is a complex system that differs in a myriad of tiny ways from any other organization. The way you work. Your customer relationships. Your people. These are different in every industry and every company. Recipes underrepresent that complexity.

Shane Parrish writes "When we set out to understand a complex system, our intuition tells us to break it down into its component pieces. But that’s linear thinking, and it explains why so much of our thinking about complexity falls short. Small changes in a complex system can cause sudden and large changes. Small changes cause cascades among the connected parts, like knocking over the first domino in a long row."

Recipes cause harm because they only prepare for a future that is in the past. By oversimplifying complexity we limit our ability to change. So how do you shift your approach from recipes to preparations?

The answer partly lies in shifting your decision-making from large decisions to small bets. Vaughn Tan puts it this way when talking about operating in uncertainty. "Take small but immediate actions that are designed to limit commitment while allowing exploration of the changing situation." Directionally you still need to be on point, but by placing smaller bets you can get a lot wrong and still be right in the end.

Let's use marketing as an example. In recessions, this is a clear, obvious discretionary item to cut. The typical plan would be to slash the marketing budget to prepare for reduced demand and save costs. It’s hard to argue with that.

But on the other hand, taking a preparation approach would seek to gather more information to help you adapt as things change. If you slash marketing, you lose the ability to collect information about how your customers are reacting. So the strategy here might be to reduce marketing spend but to increase the variance in messaging and approach. Place a series of different promotions and messaging that can be easily modified to respond to unexpected behavior.

This simple example points to the importance of creating optionality for your company. More information helps increase the hit rate in decision-making. It's your job to find ways to sift through it all and make more right bets than wrong ones.

Or as Ferran Adria would say, create more preparations, less recipes.

Consistency

“Lets say you want to win a gold medal in the Olympics. You want to learn a musical instrument. You want to learn a foreign language. You want to build Berkshire Hathaway. What’s the formula? Dogged incremental constant progress over a very long time frame. Look how simple this is. This is above genius. It’s absolutely above genius because you can understand it. This isn’t somebody drawing all these formulas and things up here about, you know, how numbers multiply and amplify over time. The problem that human beings have is we don’t like to be constant. Think of each one of those terms. Dogged incremental constant progress over a very long time frame. Nobody wants to be constant. We’re the functional equivalent of Sisyphus pushing his boulder up the mountain. You push it up half way, and you go, ‘Aw, I’ll come back and do this another time.’ It goes back down. ‘I’ve got this great idea, I’m going to really work hard on it.’ You push it up half way and,’ Aw, you know I’ll get back to this next month.’ This is the human condition. In geometric terms this is called variance drain. Whenever you interrupt the constant increase above a certain level of threshold you lose compounding, you’re no longer on the log curve. You fall back onto a linear curve or God forbid a step curve down. You have to be constant.”

-Peter Kauffman

The above quote is from an excellent speech by Peter Kauffman. You can read or listen to the entire speech here. This resonated with me because it speaks to a proven process that is true of most things; strengthening relationships, creating products, forming teams, crafting disciplines, learning skills and building companies.

Dogged incremental constant progress over a very long time.

That sounds intimidating, but it is also tremendously freeing. The formula is there. Consistent, intentional progress is not only attainable, it can be systematic. This is the underpinning of our strategy of Learn Better, Faster. But here is the secret – that progress can compound the more additive energy that is poured into it.

Drip, drip, drip.

Discovering 'Product Alpha' and How It Can Help You Design Better Products

Are you familiar with the term alpha in investing?

Alpha is a way to track the performance of a specific investment. It measures the excess return relative to the return of some sort of benchmark. For example, if you invest in a stock that returns 15% in a given year, while the Fortune 500 index returns 10%, your fund would have achieved positive alpha of +5 for the year. Basically, you beat the market (time to plan for retirement!).

So What is Product Alpha?

Here is how we define it: Product alpha is the measurement of value that a differentiating design process creates compared to a benchmark competitive process.

Most product design firms (including my firm, Versett) go to great lengths to describe the methodology and quality of their proprietary processes. But these procedures are only one part of delivering consistent results. More importantly, it is how your process delivers value above and beyond the competitive baseline. If everyone is doing “best practices”, how are you delivering results above and beyond that?

So while you can do all of the design thinking exercises, post-mortems, discovery sessions, process checklists, and everything else, these incremental improvements do not tackle a fundamental problem—most of the market is doing it too.

Practically, it means that while the strategic, design, and engineering tactics you employ are consistently adapting to best practices, to truly "beat the market" and create positive product alpha, you have to incorporate proprietary tooling, processes, and strategies that are significantly better and differentiated. Put another way, it is not the sophistication of the process that matters, it's the quality and outcomes of the process relative to the competition.

Is it possible to consistently outperform other firms? I think it is, but it often requires reframing how you think about your customers, business model, and ultimately the products you offer and how effectively you adapt to a shifting landscape. This is especially true in digital environments.

Most mobile apps, e-commerce sites, and digital platforms fail to deliver superior relative performance because they were created using the same flows, the same practices, by the same types of people placing post-its on a whiteboard. These processes are not inherently wrong, but they result in zero product alpha.

So how do you increase the frequency of delivering positive product alpha across your organization? Here are a few of the systematic initiatives we have found helpful when thinking through this with several of our clients.

- Learn Better, Faster

One of the greatest, sustainable competitive advantages a firm can develop is the ability to consistently learn and interpret knowledge faster than your competition. (Knowing what to learn is another tricky part). This can be systematically applied throughout your organization. - Leverage Data

You can only benchmark performance if you fully understand the metrics of the business. Be analytical, but more importantly, define how to leverage this data to drive decision-making criteria across your products. - Avoid Outcome Bias

Howard Marks of Oaktree Capital has a saying: “The fact that something worked, doesn’t mean it was the result of a correct decision, and the fact that something failed, doesn’t mean the decision was wrong.” Find ways to understand the real underpinnings of successes and failures in your product decision making.

These are just a few of the thousands of factors that directly contribute to positive product alpha. To begin marking progress holistically, audit the strategic frameworks that you are currently employing across your organization.

Ask yourself—which processes consistently deliver results? Which ones are failing? Do we follow a process just because it's best practice? These will help guide you to better understand which levers to pull to build a more effective model for product alpha.

It's an endless pursuit, but a rewarding one.

Setting up a 'Personal Learning OS'

I have spent way too much time trialling different tools and platforms to find a good balance of how to ingest, manage, recall and enjoy interesting content. A few people have asked how I have set things up, so after a lot of trial and error, here is where I have landed (so far).

Basic Set-up

I use Instapaper and Kindle as my primary reading tools. Everything on the web worth remembering I save to Instapaper and I do almost all my reading on Kindle. I use Castro for podcasts.

I highlight passages extensively, trying to focus on only the most salient and essential parts that I want to be able to reference in the future or remember. Over time I have begun to highlight less and less from each source, being a bit more judicious in an effort to increase the signal to noise ratio of these reference passages.

Both Kindle and Instapaper highlights can be synced through the amazing aggregator platform Readwise. I have Readwise set-up to email me daily with a collection of highlights from all of the books and articles I have ever read. (You can fine-tune the settings to increase or decrease the frequency for each book or article)

This set up gives you a light form of ‘spaced repetition’ learning which I find incredibly helpful in retaining information. It’s also surprising how much things I forget over time. The daily reminders help keep it at the forefront of the mind and I enjoy the serendipity of discovering passages that would have completely been lost in the ether.

Of course, all of this only matters if you find good source material to begin with. For me, the best conduit is Twitter, which I work constantly on curating and pruning to ensure a steady stream of interesting things. If edited properly, Twitter can be an incredible tool for collecting information across a wide spectrum of perspectives and viewpoints. It takes work to maintain, but it is endlessly powerful if you stick with it. (I also block a lot of terms that I don’t want to be distracted by. Politicians, news events, the TV show of the moment etc. I love pop culture, but I try and keep Twitter as pure as possible and get that ‘fix’ elsewhere)

Lately, I have also gotten into deep reading into certain “non-book” sources that catch my eye. For me, this was reading all of Howard Mark’s memos and working my way through all 24 years of Berkshire Hathaway’s annual reports. In this incredible essay, Peter Kauffman read through the entirety of Discover magazine’s cover stories to learn how the top scientists were thinking about their field.

For long-form reading, I like to read many books concurrently. I just find it easier to pick up certain types of book at different times. Meatier reads require more focus and attention, while some books I can read anywhere, so I like to have a bunch of books on the go at one time.

For podcasts, I use Castro because you can prioritize and favourite episodes, and most importantly, save excerpts of podcasts and share or save those snippets. It’s also a joy to use.

Additional Tips

- Batch read your Instapaper queue. Most things are not time sensitive, and you are better off reading when you are away from distractions and have time to digest. This is also a helpful curation tool, because after a few days you might find certain articles just don’t look as interesting. I usually do this in the morning.

- Read all books on Kindle. It took me a while to adjust to this, but I have now fully converted because of the ability to highlight key passages for retrieval later.

- Be sure to install Instapaper on all devices and edit your Share Sheets If you are an iOS user, you can edit your Share Sheet settings to make sure the Instapaper is in the in the “Top 5” items. I prefer Instapaper over Pocket because of its highlighting ability and syncing with Readwise.

- Categorize your Instapaper for easy reference If I read a particularly great article, I add it to a defined folder in Instapaper for reference later. This can be really helpful when someone is looking for information on a topic (ie Marketplaces). I just send all the links directly from the folder.

- User the Search in Instapaper and Kindle Highlights You can search both platforms for keywords and search terms. This can be hugely helpful when trying to dig up a key concept or idea.

- Prune your sources Don’t be afraid to unfollow people or unsubscribe from that podcast. Be your own editor — the content stream is too big and the good stuff can get lost in the algorithms. Filter aggressively.

A step further…

This won’t be of any interest for some of you, so read on at your own peril.

After getting hooked on Readwise emails, I decided to utilize

Anki to act as a secondary tool to better retain specific quotes, ideas and concepts that I want to really know well. Anki is essentially a digital flashcard system, where you can test your knowledge by creating custom cards and reviewing them.

When I hear or read something interesting, I create a card in Anki and review them every few days. I have the app on my home screen and use “found time” to do a quick review. I was skeptical if this would work over the long term (or if I would stick with it) but I have found it to be really addicting and a powerful tool.

After diving into the Building a Second Brain system a year ago, I still use a modified form of Tiago’s system for Evernote to capture broader business concepts and reference information I categorize key concepts (ie things like Anecdotes, Product Pricing, etc). When I read something that has significant ‘evergreen” value, I add it to the Evernote Note on the topic so it is indexable and easy to find if I need it.

Hope this helps, would love to know your system and how it changed over time.